VIVEKANANDA: The Common Thread that Runs Through the Lives of Tesla, Tolstoy, Salinger and Bernhardt

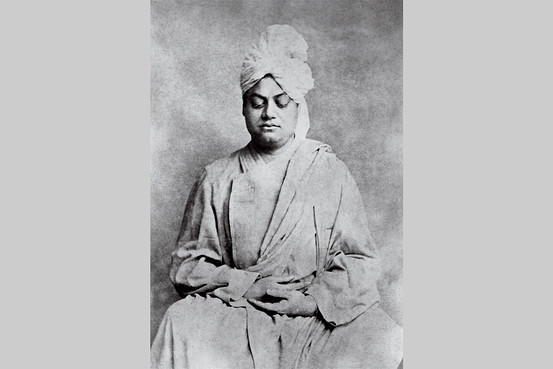

MY SWEET LORD The swami Vivekananda, the Bengali monk who brought yoga to the United States, meditating in London, in 1896. COURTESY OF VEDANTA SOCIETY

What Did J.D. Salinger, Leo Tolstoy, and Sarah Bernhardt Have in Common?

The surprising—and continuing—influence of Swami Vivekananda, the pied piper of the global yoga movement

By A. L. Bardach

Updated March 30, 2012

The Wall Street Journal

By the late 1960s, the most famous writer in America had become a recluse, having forsaken his dazzling career. Nevertheless, J.D. Salinger often came to Manhattan, staying at his parents’ sprawling apartment on Park Avenue and 91st Street. While he no longer visited with his editors at “The New Yorker,” he was keen to spend time with his spiritual teacher, Swami Nikhilananda, the founder of the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, located, then as now, in a townhouse just three blocks away, at 17 East 94th Street.

Though the iconic author of “The Catcher in the Rye” and “Franny and Zooey” published his last story in 1965, he did not stop writing. From the early 1950s onward, he maintained a lively correspondence with several Vedanta monks and fellow devotees.

After all, the central, guiding light of Salinger’s spiritual quest was the teachings of Vivekananda, the Calcutta-born monk who popularized Vedanta and yoga in the West at the end of the 19th century.

These days yoga is offered up in classes and studios that have become as ubiquitous as Starbucks. Vivekananda would have been puzzled, if not somewhat alarmed. “As soon as I think of myself as a little body,” he warned, “I want to preserve it, protect it, to keep it nice, at the expense of other bodies. Then you and I become separate.” For Vivekananda, who established the first ever Vedanta Center, in Manhattan in 1896, yoga meant just one thing: “the realization of God.”

After an initial dalliance in the late 1940s with Zen—a spiritual path without a God—Salinger discovered Vedanta, which he found infinitely more consoling. “Unlike Zen,” Salinger’s biographer, Kenneth Slawenski, points out, “Vedanta offered a path to a personal relationship with God…[and] a promise that he could obtain a cure for his depression….and find God, and through God, peace.”

Finding peace would, however, be a lifelong battle. In 1975, Salinger wrote to another monk at the New York City center about his own daily struggle, citing a text of the eighth-century Indian mystic Shankara as a cautionary tale: “In the forest-tract of sense pleasures there prowls a huge tiger called the mind. Let good people who have a longing for Liberation never go there.” Salinger wrote, “I suspect that nothing is truer than that,” confessing despondently, “and yet I allow myself to be mauled by that old tiger almost every wakeful minute of my life.”

It was his daily mauling by the “huge tiger” and his dreaded depressions that led Salinger to abandon his literary ambitions in favor of spiritual ones. Salinger—who appears to have had a nervous breakdown of sorts upon his return from the gruesome front lines of World War II—subscribed to Vivekananda’s view of the mind as a drunken monkey who is stung by a scorpion and then consumed by a demon. At the same time, Vivekananda promised hope and solace—writing that the “same mind, when subdued and controlled, becomes a most trusted friend and helper, guaranteeing peace and happiness.” It was precisely the consolation that Salinger so desperately sought. And by 1965 he was ready to renounce his once gritty pursuit of literary celebrity.

Although all but forgotten by America’s 20 million would-be yoginis, clad in their finest Lululemon, Vivekananda was the Bengali monk who introduced the word “yoga” into the national conversation. In 1893, outfitted in a red, flowing turban and yellow robes belted by a scarlet sash, he had delivered a show-stopping speech in Chicago. The event was the tony Parliament of Religions, which had been convened as a spiritual complement to the World’s Fair, showcasing the industrial and technological achievements of the age.

On its opening day, September 11, Vivekananda, who appeared to be meditating onstage, was summoned to speak and did so without notes. “Sisters and Brothers of America,” he began, in a sonorous voice tinged with “a delightful slight Irish brogue,” according to one listener, attributable to his Trinity College–educated professor in India. “It fills my heart with joy unspeakable…”

Then something unprecedented happened, presaging the phenomenon decades later that greeted the Beatles (one of whom, George Harrison, would become a lifelong Vivekananda devotee). The previously sedate crowd of 4,000-plus attendees rose to their feet and wildly cheered the visiting monk, who, having never before addressed a large gathering, was as shocked as his audience. “I thank you in the name of the most ancient order of monks in the world,” he responded, flushed with emotion. “I thank you in the name of the mother of religions, and I thank you in the name of millions and millions of Hindu people of all classes and sects.”

Annie Besant, a British Theosophist and a conference delegate, described Vivekananda’s impact, writing that he was “a striking figure, clad in yellow and orange, shining like the sun of India in the midst of the heavy atmosphere of Chicago…a lion head, piercing eyes, mobile lips, movements swift and abrupt.” The Parliament, she said, was “enraptured; the huge multitude hung upon his words.” When he was done, the convocation rose again and cheered him even more thunderously. Another delegate described “scores of women walking over the benches to get near to him,” prompting one wag to crack wise that if the 30-year-old Vivekananda “can resist that onslaught, [he is] indeed a god.”

“No doubt the vast majority of those present hardly knew why they had been so powerfully moved,” Christopher Isherwood wrote a half century later, surmising that a “strange kind of subconscious telepathy” had infected the hall, beginning with Vivekananda’s first words, which have resonated, for some, long after. Asked about the origins of “My Sweet Lord,” George Harrison replied that “the song really came from Swami Vivekananda, who said, ‘If there is a God, we must see him. And if there is a soul, we must perceive it.’ ”

The teachings of Vedanta are rooted in the Vedas, ancient scriptures going back several thousand years that also inform Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. The Vedic texts of the Upanishads enshrine a core belief that God is within and without—that the divine is everywhere. The Bhagavad Gita (Song of God) is another sacred text or gospel, whereas Hinduism is actually a coinage popularized by Vivekananda to describe a faith of diverse and myriad beliefs.

Vivekananda’s genius was to simplify Vedantic thought to a few accessible teachings that Westerners found irresistible. God was not the capricious tyrant in the heavens avowed by Bible-thumpers, but rather a power that resided in the human heart. “Each soul is potentially divine,” he promised. “The goal is to manifest that divinity within by controlling nature, external and internal.” And to close the deal for the fence-sitters, he punched up Vedanta’s embrace of other faiths and their prophets. Christ and Buddha were incarnations of the divine, he said, no less than Krishna and his own teacher, Ramakrishna.

‘He is the most brilliant wise man,’ Leo Tolstoy waxed. ‘It is doubtful another man has ever risen above this selfless, spiritual meditation.’

Although Vivekananda was a Western-educated intellectual of encyclopedic erudition, “the descendant of 50 generations of lawyers,” as he would say, Ramakrishna was for all intents and purposes illiterate. Born Gadadhar Chattopadhyay, Ramakrishna had not an iota of interest in schooling beyond the study of scripture and prayer. Fortunately, that amply met the job requirements of his post as a priest at the Dakshineswar Kali Temple. According to numerous firsthand, contemporaneous accounts, Ramakrishna—who is revered as a saint in much of India and as an avatar by many—spent a good deal of his short life in samadhi, or an ecstatic state. On a daily basis, sitting or standing, he was often observed slipping into a transported state that he described as “God consciousness,” existing with neither food nor sleep. He died in 1886 at age 50.

Though Ramakrishna spoke in a village idiom, invoking homespun local parables, word about the “Bengali saint” spread through the chattering classes of India in the 1870s like a monsoon. Many who flocked to him—and declared him a divine incarnation—were educated as lawyers, doctors and engineers and were often the graduates of British-run Christian schools. His closest and most influential disciple, however, was Vivekananda (born Narendranath Datta in 1863 to an affluent family), whom he charged with carrying the message of Vedanta to the world.

Certainly, a smattering of Eastern thought had already traveled to the West before Vivekananda’s arrival in the U.S. In the 1820s, Ralph Waldo Emerson had snared a copy of the Bhagavad Gita and found himself enchanted. “I owed a magnificent day to the Bhagavad Gita,” Emerson wrote in his journal in 1831. The Gita would inform his Transcendentalist essays, in which he wrote of the “Over-Soul,” that part of the individual that is one with the universe—invoking the Vedantic precepts of the Atman and Brahman. (In a tidy historical twist, one of Emerson’s relatives, Ellen Waldo, became a devotee of Vivekananda, and faithfully transcribed the dictated text of his first book, “Raja Yoga,” in 1895.)

Emerson’s student and fellow Transcendentalist, Henry David Thoreau, would study Indian thought even more avidly and crafted his own practice—living as a secular monk, as it were, by Walden Pond. In 1875, Walt Whitman was given a copy of the Gita as a Christmas gift, and it is heard unmistakably in “Leaves of Grass” in lines such as “I pass death with the dying and birth with the new-wash’d babe, and am not contained between my hat and my boots.” Though the two never met, Vivekananda hailed Whitman as “the Sannyasin of America.”

The Academy, however, was a bit slower to embrace Eastern thought and literature. It wasn’t until after an electrifying lecture by Vivekananda at Harvard’s Graduate Philosophical Club on March 25, 1896, that Eastern Philosophy departments became a staple at Ivy League colleges.

Fascinated by the erudite and polyglot monk—who could pass an entire day sitting motionless in silent meditation—the esteemed philosopher William James roped in many of his colleagues, students and friends to attend Vivekananda’s Harvard lecture. They were not disappointed. “The theory of evolution, and prana [energy] and akasa [space] is exactly what your modern science has,” their exotic visitor blithely informed them. Nor were they unamused. When asked, “Swami, what do you think about food and breathing?” he replied, “I am for both.” The evening ended with the turbaned monk, “dressed in rich dark red robes,” receiving an offer to chair Harvard’s new department. Columbia University promptly made its own bid for Vivekananda—who declined both, noting his vows of renunciation.

At a dinner party in his honor the following night, William James and Vivekananda scurried off to a corner by themselves, where they were observed nattering away until midnight. The next morning, James sent word inviting him to dinner at his own home that evening. And over the next week, James would dash into Boston to hear his other lectures.

“He has evidently swept Professor James off his feet,” wrote a Harvard colleague. Indeed, the eminent scholar was deferential to a fault with his newfound Bengali friend, referring to him as Master. More important, in his seminal book “The Varieties of Religious Experience,” James relied upon Vivekananda’s “Raja Yoga,” a treatise on the discipline of meditation practice from which he quoted extensively: “All the different steps in yoga are intended to bring us scientifically to the superconscious state, or samadhi.”

Unbeknownst to him, Vivekananda had hit the piñata of influence: James was arguably the country’s premier intellectual. And it hardly hurt that his brother was the master novelist Henry James.

Along with the James brothers, a half dozen socially prominent and wealthy women immeasurably facilitated the visiting monk—who not infrequently encountered some racism on his U.S. lecture tours. Sara Bull in Cambridge, Josephine MacLeod in New York City, and Margaret Noble in London would set up salons and avidly spread the word—and even followed him to India. With the vast contacts and shrewd networking of these women, his talks in Cambridge and Manhattan became standing-room-only affairs attended by the cognoscenti of the day, assorted seekers, and all manner of movers and shakers—from Gertrude Stein, one of James’s students, to John D. Rockefeller. Blessed with “the power of personality,” as Henry James would say, Vivekananda was the ideal missionary to pitch the message of Vedanta.

During his lifetime, Vivekananda had another enthusiast in Leo Tolstoy, the titan of Russian letters. “He is the most brilliant wise man,” Tolstoy gushed after devouring “Raja Yoga” in 1896 in a single sitting and reporting it to be “most remarkable… [and] I have received much instruction. The precept of what the true ‘I’ of a man is, is excellent…Yesterday, I read Vivekananda the whole day.”

Not long before his death, Tolstoy was still waxing about Vivekananda. “It is doubtful in this age that another man has ever risen above this selfless, spiritual meditation.”

Tolstoy and Vivekananda never met, but the opera diva Emma Calvé and the great tragedienne Sarah Bernhardt sought him out and became his lifelong friends.

Scores of women walked over benches to get near him, prompting one wag to crack, if Vivekananda ‘can resist that onslaught, then he is indeed a god.’

Bernhardt, in fact, introduced him to the electromagnetic scientist Nikola Tesla, who was struck by Vivekananda’s knowledge of physics. Both recognized they had been pondering the same thesis on energy—in different languages. Vivekananda was keenly interested in the science supporting meditation, and Tesla would cite the monk’s contributions in his pioneering research of electricity. “Mr. Tesla was charmed to hear about the Vedantic prana and akasha and the kalpas [time],” Vivekananda wrote to a friend. “He thinks he can demonstrate mathematically that force and matter are reducible to potential energy. I am to go to see him next week to get this mathematical demonstration. In that case Vedantic cosmology will be placed on the surest of foundations.” For the monk from Calcutta, there were no inconsistencies between science, evolution and religious belief. Faith, he wrote, must be based upon direct experience, not religious platitudes.

More presciently, he warned that India would remain a vanquished, impoverished land until it “elevated” the status of women. And while he admonished Westerners for their preoccupation with the material and the physical, he famously advised a sickly young devotee to toughen himself with athletics: “You will be nearer to heaven playing football than studying the Bhagavad Gita.”

Vivekananda’s influence bloomed well into the mid-20th century, infusing the work of Mahatma Gandhi, Carl Jung, George Santayana, Jane Addams, Joseph Campbell and Henry Miller, among assorted luminaries. And then he seemed to go into eclipse in the West. American baby boomers—more disposed to “doing” than “being”—have opted for “hot yoga” classes over meditation. At some point, perhaps in the 1980s, an ancient, profoundly antimaterialist teaching had morphed into a fitness cult with expensive accessories.

Moreover, a few American academics have recently taken to scrutinizing Vivekananda and Ramakrishna through a Freudian prism, offering up speculative theories of sexual repression. In turn their critics respond that the two titans from Calcutta are incomprehensible via simplistic Freudian prisms. To understand the unconditional celibacy of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, they argue, requires fluency in 19th-century Bengali and a decidedly non-Western paradigm.

Supporting this view were Christopher Isherwood and his friend Aldous Huxley, who wrote the introduction to the 1942 English-language edition of “The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna,” a firsthand account (originally published in India in 1898) described by Huxley as “the most profound and subtle utterances about the nature of Ultimate Reality.” Nikhilananda, Salinger’s guru, did the translation, with assistance from Huxley, Joseph Campbell and Margaret Wilson, the daughter of the late president.

Huxley and Isherwood were introduced to Vedanta in the Hollywood Hills in the late 1930s by their countryman, the writer Gerald Heard. In a fitting counterpart to the New York Center, the Hollywood Vedanta society was likewise run by a scholarly and charismatic monk, Prabhavananda, who initiated the English trio of writers.

Like Nikhilananda, Prabhavananda was a magnet for the intelligentsia, and his lectures often attracted the likes of Igor Stravinsky, Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh and W. Somerset Maugham (and led to his writing “The Razor’s Edge”). Inspired by Isherwood—who briefly lived at the center as a monk—Greta Garbo asked if she too might move in. Told that a monastery accepts only men, Garbo became testy. “That doesn’t matter!” she thumped. “I’ll put on trousers.”

Henry Miller, who made headlines with his torrid and banned “Tropic of Cancer,” visited with Prabhavananda at the Hollywood center, devoured a small library of Vedanta books and settled down in Big Sur in 1944. Throughout his memoir, “The Air Conditioned Nightmare,” Miller invokes Vivekananda as the great sage of the modern age and the consummate messenger to rescue the West from spiritual bankruptcy.

Isherwood’s commitment to Vedanta, like Salinger’s, was unswerving and lifelong. Over the next 20 years, he co-translated with Prabhavananda the Bhagavad Gita, Patanjali’s “Yoga Aphorisms” and Shankara’s “Crest Jewel of Discrimination,” and was the author of several books and tracts on Vivekananda and Ramakrishna.

Huxley, however, in his final years turned over his spiritual quest to his second wife, Laura, and pharmaceuticals—an unequivocal no-no among Vedantins. Believing he had found a shortcut to samadhi, the great man had his wife inject him with LSD on his deathbed. “Aldous was the most brilliant man I ever met,” sighed one monk, “but he lacked discrimination.”

Of all the literary lions captivated by Vivekananda and Vedanta, J.D. Salinger perhaps made the fullest commitment and sacrifices. In 1952, Salinger exhorted his British publisher to pick up the English rights of the Gospel, calling it “the religious book of the century.”

At the peak of his fame in 1961, Salinger delivered a warmly inscribed copy of “Franny and Zooey,” which is saturated in Vedantic thought and references, to his guru Nikhilananda, who by then had formally initiated him as a devotee. Salinger confided to Nikhilananda that he intentionally left a trail of Vedantic clues throughout his work from “Franny and Zooey” onward, hoping to entice readers into deeper study.

The two men often met at the 94th Street center, where they would discuss the spiritual challenges of renunciation. Salinger would also embark on “personal retreats” at the Vedanta center in Thousand Island Park in the St. Lawrence River. There he would stay in the cottage where Vivekananda had lived and held retreats in the late 1890s.

In January 1963, at the New York celebration of Vivekananda’s 100th birthday—presided over by the secretary-general of the United Nations, U Thant—Salinger sat front and center at the banquet table. A few weeks later, he published “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction,” two exquisitely wrought novellas in which the suicide of Seymour, arguably Salinger’s alter ego, is the catalyzing event. “I have been reading a miscellany of Vedanta all day,” begins one entry in Seymour’s diary in “Raise High.” In Seymour, the narrator declares, “I tend to regard myself as a fourth-class Karma Yogini, with perhaps a little Jnana Yoga thrown in to spice up the pot.”

In Salinger’s last published work, “Hapworth 16, 1924,” in 1965 in “The New Yorker,” Seymour bursts into a manic tribute to Vivekananda. “Raja-Yoga and Bhakti-Yoga, two heartrending, handy, quite tiny volumes, are perfect for the pockets of any average, mobile boys our age, by Vivekananda of India.”

And then America’s beloved novelist stopped publishing. “Name and fame,” eschewed by Ramakrishna, no longer was the ticket for the increasingly hermetic Salinger. His ferocious literary ambition was now supplanted by what appears to have been a diligent, albeit eccentric, spiritual quest for the next four decades—until his death in 2010.

While Salinger is depicted by many chroniclers and contemporaries as an ornery crank, four letters, approved by Salinger’s estate for use by the New York Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, suggest a man of singular devotion and renunciation: “I read a bit from the Gita every morning before I get out of bed,” he wrote to Nikhilananda’s successor swami at the New York center in 1975.

Salinger also conducted a long correspondence with Marie Louise Burke, who compiled a six-volume history of Vivekananda’s visits to the West. Burke was as serious a seeker as Salinger and as devoted as a nun: Indeed, she took the monastic name Sister Gargi. Nevertheless, the nervous, sometimes paranoid Salinger fretted that she might profit from their letters. Unfortunately, Burke proved her fidelity to her friend by burning them.

In between his two treks to the West, Vivekananda returned to India and founded the Ramakrishna Order as both a monastery and a service mission. Today it is among the largest philanthropic organizations in India—providing food, medical assistance and disaster relief to millions. His prescription for his countrymen, however, who had been demoralized by colonialism, was to borrow a page from the West, he said, and instill itself with the “can do” spirit of Americans. “Strength! Strength is my religion!” he exhorted. “Religion is not for the weak!”

India has scheduled a yearlong party to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Vivekananda’s birth, beginning on January 12, 2013. There will be plenty of readings of his four texts on yoga as a spiritual discipline. Nine volumes chronicle his talks, writings and ruminations, from screeds against child marriage to Milton’s “Paradise Lost” to his pet goats and ducks. But if there were a single takeaway line that boils down his teachings to one spiritual bullet point, it would be “You are not your body.” This might be bad news for the yoga-mat crowd. The good news for beleaguered souls like Salinger was Vivekananda’s corollary: “You are not your mind.”

In a 1972 letter to the ailing Nikhilananda in the last year of his life, Salinger seemed to be saying as much.

“I sometimes wish that the East had deigned to concentrate some small part of its immeasurable genius to the petty art of science of keeping the body well and fit. Between extreme indifference to the body and the most extreme and zealous attention to it (Hatha Yoga), there seems to be no useful middle ground whatever.”

Salinger went on to express his gratitude to the man who had guided him out of his “long dark night.” “It may be that reading to a devoted group from the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna is all you do now, as you say, but I imagine the students who are lucky enough to hear you read from the Gospel would put the matter rather differently. Meaning that I’ve forgotten many worthy and important things in my life, but I have never forgotten the way you used to read from, and interpret, the Upanishads, up at Thousand Island Park.”

By then, Salinger had not published in some time. Nor would he again. Nor did he seem to miss it

___

https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303404704577305581227233656